If you’re over 20, chances are your true passions won’t change much. People’s fundamental preferences tend to remain consistent into adulthood. If you currently feel a strong affinity for something, it’s likely to endure.

Given that, suppressing such feelings will only lead to prolonged suffering, and it will not fade away even if ignored.

So, you are left with one option: face them now.

“But wait, what if we can’t find something we’re passionate about?”

I can almost hear this question from many young people. You might even be one of them.

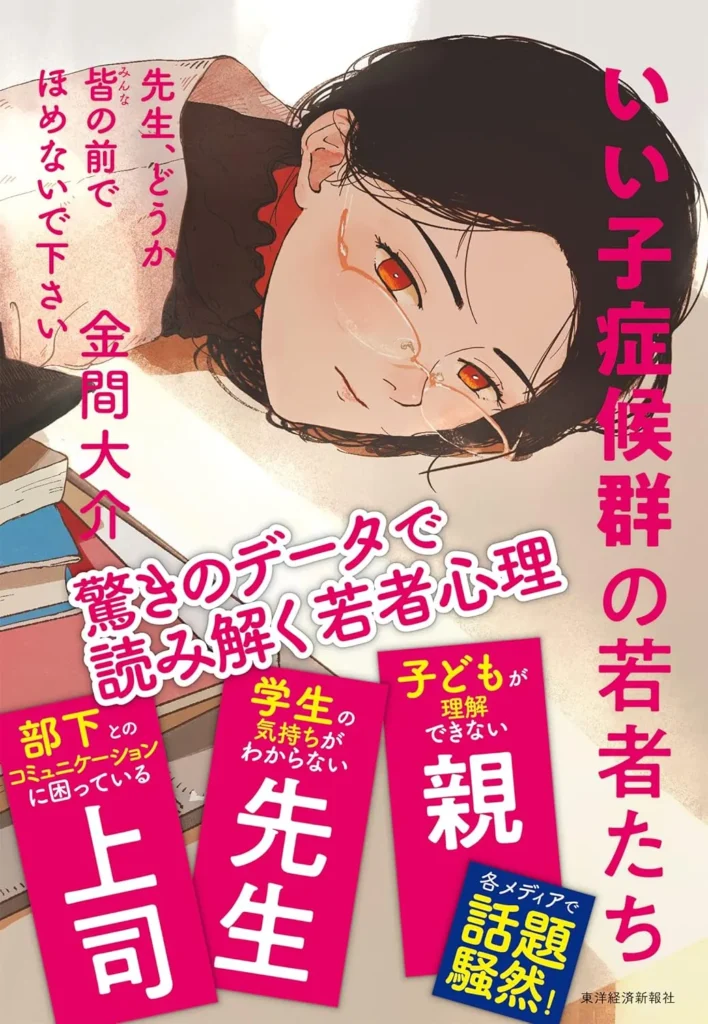

This book, “Please, Teacher, Don’t Praise Me in Front of Everyone: Young People with Good Kid Syndrome,” offers guidance to those who believe they have no passions, lack vitality, or feel resigned to a life where they lack control, showing them how to break free from that state.

The Book in 3 Sentences

- The book explores the phenomenon of the “good child syndrome” prevalent in Japanese society, where young individuals feel pressured to conform to societal expectations of perfection and obedience.

- Through interviews and analysis, the book delves into the struggles and psychological effects experienced by these youths as they navigate the pressures of academic success, family dynamics, and societal norms.

- It offers insights into the challenges of maintaining individuality and mental well-being within a culture that prioritizes conformity and external validation.

Impressions

How Did I Discover It?

While researching topics for my Quora responses, I came across a summary of the book online. Its title resonated with one of my Quora responses, prompting my curiosity. I decided to take a read to see what it had to offer.

Who Should Read It?

I would recommend this book to anyone interested in exploring the psychological and social dynamics of youth in Japanese society, particularly those struggling with the pressures of conforming to societal expectations.

It’s also beneficial for educators, parents, and counselors seeking insights into the challenges faced by young individuals striving for perfection and validation within their cultural context.

How the Book Changed Me

This spring marks my fourth year since I graduated from university.

Nevertheless, I found many aspects of the author’s portrayal of students resonating with the community I was surrounded by:

- Like how classes often fall silent when the professor seeks opinions.

- Or the expectation to sit with classmates or club members in lecture halls or the cafeteria, making it uncomfortable for those who prefer solitude.

- And how job hunting isn’t so much about what you want to do, but more about proving the skills others expect of you, leading many to prepare for internships and attend company briefings in pursuit of offers from prestigious (high-paying) firms.

I was born in Tokyo and attended local schools from elementary to high school. During my second year of high school, I left to study abroad in the United States. Upon returning, I attended a university in Tokyo and now work as a company employee in the city.

The “good child” depicted in the book seemed like a reflection of my early teenage self.

When I was 12, I passed the entrance exam to enroll in a prestigious private school, which was “my first choice.”

My soul felt drained after enduring tearful outbursts and rebellious behavior during rigorous cram school sessions. Despite the joy of acceptance, I had lost touch with my emotions by the time I started junior high:

- I was supposed to attend the junior high next to my elementary school, wearing the same uniform as my classmates whom I grew up with since nursery. So why am I willingly traveling an hour away to a community so far apart?

- My parents say it’s for my own good, but it was my mother who encouraged me to take the entrance exam. I owe my existence to my parents and can’t bear to disappoint them. Amidst these conflicted days, I ended up taking the exam just as my parents wanted. And unfortunately, I passed.

- My parents are thrilled. “Why do you look so deflated? You passed!” they say. But wait, my heart isn’t in it. What am I supposed to do as I grow older? I haven’t even lived 20% of my life, yet I feel this despair. I’m exhausted to my core.

From the upper grades of elementary school to the first half of junior high, it felt like being pushed into a dark pool, struggling to lift my chin above water, and constantly fearing the waves coming from all sides.

However, from this age onwards, I managed to escape this darkness, acknowledge my weaknesses and shortcomings, and gradually learn to accept myself, including those aspects I once disliked.

This book provided me with the opportunity to reflect on that journey.

I began preparing to study abroad in high school in my third year of junior high.

During my second year of junior high, I watched the Disney movie “High School Musical” in a music class and felt a desire to experience American high school life. Unlike my previous activities and exam preparations, this was one of the first times I felt a genuine desire to pursue something on my own.

It was an intuitive feeling at the time, but looking back now, I see I wanted to escape from what I perceived as the “social norms” of my surroundings. I wanted to venture into a world unknown to my parents, to experience something beyond their expectations, and to make experiences that couldn’t be measured by their standards.

It took time to gain my parents’ approval, and the decision to study abroad was finalized in my second year of high school.

However, from the day I expressed my desire to study abroad, each light in the pool of darkness surrounding me began to illuminate. Gradually, I could grasp my current position and destination.

When I relate to the young people depicted in the book, it might be more accurate to say that I became “less afraid” of grasping my sense of worth and asking big questions about my life. I remember the courage that blossomed within me, wanting to decide my own life and walk my own path on my own feet.

Since going to the U.S. for high school, returning home, attending university, finding a job, and now.

It would be a lie to say that I am not conscious of the expectations of my parents and those around me, but it is no longer something that instills fear in me; rather, it is a source of strength.

Ultimately, what they want is for me to be happy, meaning they want me to be content with my choices and embrace each day. Now, I can confidently place myself as the protagonist of my own life, without fear.

Through this book, I’ve reflected on how important and precious it is to be who I am today, just being “peaceful” and “normal.”

My Top 5 Quotes

Usually, I only share three favorite quotes from books I review.

However, since this book hasn’t been translated into languages besides Japanese, I’ll share 5 quotes that I found particularly insightful.

These quotes capture the thought processes of youths in Japan and their societal significance.

- “For young people suffering from the ‘good child syndrome,’ there’s something much more difficult to accept than a society based on academic credentials. It’s something that makes facing such issues seem preferable to them, something that promotes the idea that academic credentials are paramount. It’s the method mentioned earlier: ‘thoroughly assessing students’ individuality and abilities and taking time to hire them.’ For students who prefer not to stand out, blend in, avoid competition as much as possible, and lack confidence in themselves, such a hiring process is nothing but an overwhelming burden.” (いい子症候群の若者にとって、学歴社会などよりもずっと受け入れがたいものがある。そんなことに向き合うくらいなら学歴社会上等と思わせるもの。 それは前述した「学生の個性や能力をじっくりと見極め、時間をかけて採用する方法」だ。なるべく目立たなく、なるべく横並びで、なるべく競争せず、なおかつ自分に自信がない学生にとって、こんな採用プロセスは圧のかたまりでしかない。)

- “But not deciding your life means someone else will decide it for you. And that someone isn’t always filled with wisdom, kindness, or respect. No, even someone with wisdom won’t always understand what you want. It could be quite the opposite.” (でも、自分で自分の人生を決めないということは、ほかの誰かがあなたの人生を決めるということだ。その誰かとは、良識に溢れ、心優しく、尊敬できる人間ばかりではない。いや、良識に溢れる人間だって、いつもあなたの望むことを察してくれるわけではない。むしろその真逆だってありうる。)

- “You call that state ‘normal.’ When you say, ‘I don’t desire anything special at all. If I can just live peacefully every day, that’s enough for me. I really don’t have any desires.’ If that’s what you mean by ‘normal,’ stop joking. Wake up from your dreams already. What you call ‘peaceful’ or ‘normal’ is the highest level of treatment available in Japan right now.” (あなたはそんな状態を「普通」と呼ぶ。「自分は特別なことは全然望まないです。毎日、平穏に過ごせればそれで、普通で十分と思ってるんで。ほんと、欲ないですよね」と言うときの「普通」のことだ。冗談じゃない。いい加減に夢から目覚めなさい。あなたの言う「平穏」や「普通」とは、今の日本で得られる最上級の待遇にある。)

- “No matter how weak your self-esteem, how introverted you may be, or how lacking in confidence you may be, even if you prefer to sit in a corner during meetings and discussions quietly, there’s one thing you should decide for yourself: what you learn. Even if you follow the crowd and succumb to peer pressure in other aspects, never compromise on what you learn and why. The reason being, as repetitive as it may sound, purposeful learning strengthens you.” (どんなに自己肯定感が弱く、内向的で、有能感に乏しく、打ち合わせや会議の席では端っこでおとなしくしていたいタイプだとしても、学習のことだけは自分で決めるべきだ。ほかのことは空気に従い、同調圧力に流されたとしても、何のために、何を学習するか、ということだけは絶対に譲らないでほしい。その理由は、繰り返しになるが、目的を持った学習は自分を強くしてくれるからだ。)

- “When people decide on the course of their lives, there are only three factors to consider: ① Things, ② People, and ③ Places. The weighting of these three factors varies from person to person, and the balance determines the final priority. Those who lack interest in things often prioritize either ② or ③. It’s perfectly fine to think about the future based on people or places, saying things like, ‘I want to work with these kinds of people’ or ‘I want to do something in this place.’” (人が人生の進路を決める際、考慮する要素は実は3つしかない。①コト、②ヒト、③場所だ。3つの重み付けは人によって異なり、そのバランスが最終的な優先順位となる。ことに興味を持てない人は、②か③の重み付けが高いのだ。「こういうヒトたちと一緒に働きたい」「この場所で何かしたい」といった風に、人や場所をきっかけに、将来を考えてみて全然構わない。)

Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments below.

If you want to receive notifications whenever I publish a new article, follow me on Medium.

I’ll see you soon in my next piece.